The Sahagun family keeps most of their belongings in shoeboxes and plastic crates. “This way, we move faster when the floods come,” said Jajazz, the family’s 11-year old son. Jajazz lives in the mountainous Rizal province, but his family makes a living as fishermen in Cardona, a municipality connected to the Laguna de Bay lake.

When storms sweep through their area, the Sahaguns fetch their boxes and hike as far uphill as they can. Floods have already claimed the family’s home four times since Jajazz was born.

Elsewhere, Dodie Agrabio had to sleep on the sweaty, bloodstained floors of a boxing gym. The fighter-turned-coach travels from Malabon, Bulacan, to Marikina City for work, but flooding makes it impossible for him to return home. At 10:37 p.m., he returned to the gym and spent the night there. During severe typhoons, it takes days before Agrabio can return to his wife and children.

Weak flood controls regularly cost Filipinos their lives, homes, and livelihoods. Recent investigations into substandard flood control “projects” have discovered sacks stuffed with sand, collapsing dikes, and nonexistent floodwalls.

There’s a “chasm between plan and reality” when it comes to flood controls, Dr. Ramon Abracosa tells ABS-CBN.com.

Abracosa completed his Stanford University doctorate and master’s degrees in Infrastructure Planning and Management. A professor at the Asian Institute of Management, Abracosa also studied Water Resources Engineering at the University of the Philippines. He adds that the Philippines is stuck in “a cycle of reactive, short-term solutions, leading to recurring devastation.”

In the Philippines, “there’s a severe disconnect between plans and actual project implementation,” Abracosa said. Most people are unaware of how flooding even occurs to this degree, or what proper flood controls should look like. Worsening climate change and decades of disastrous urban planning choices have made the situation so bleak that there is no longer a master plan capable of resolving the issue.

ABS-CBN.com spoke to experts to learn how the country became extremely vulnerable to floods, and what needs to be done about it.

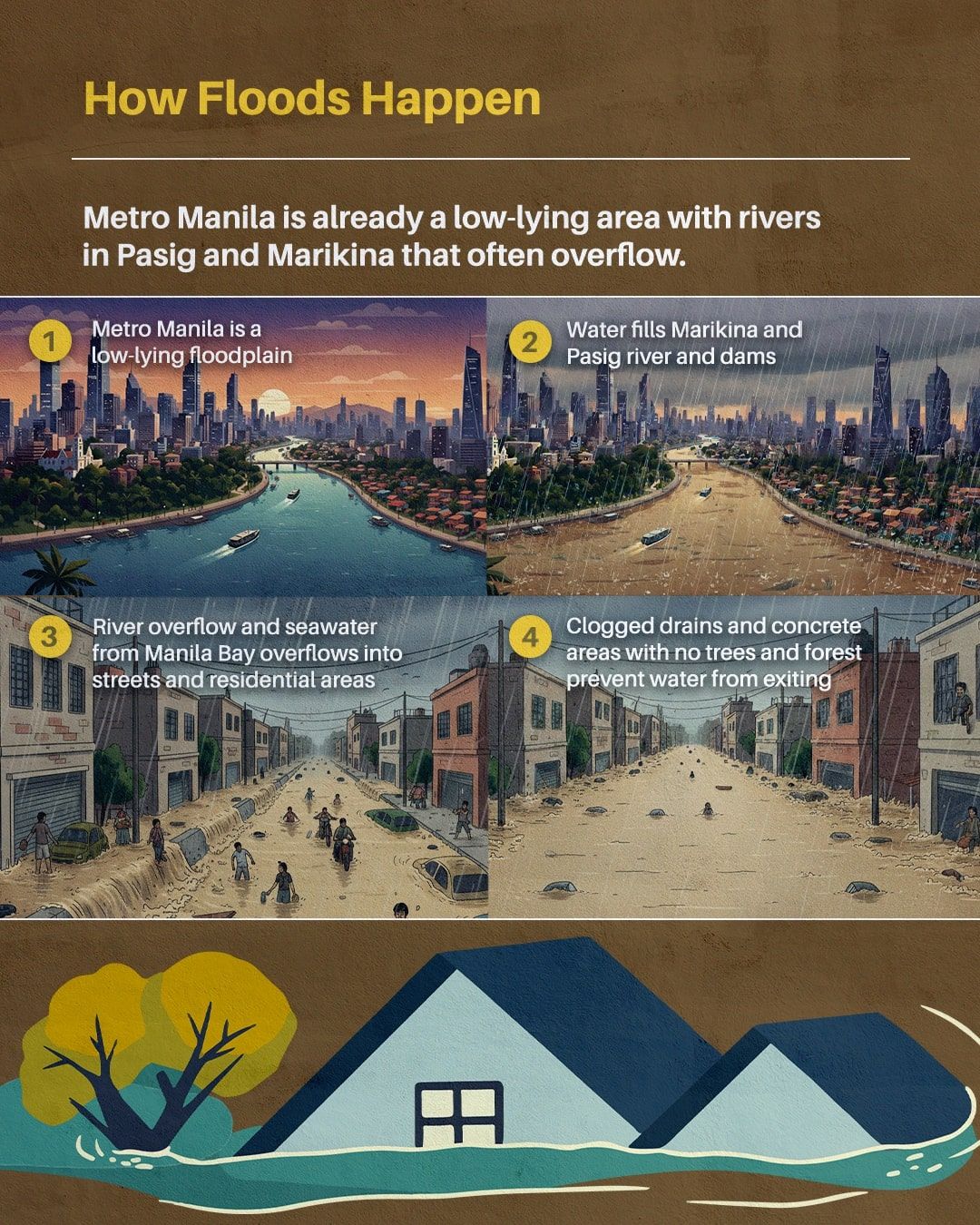

Several geographic disadvantages play a role: Metro Manila is already a low-lying area with rivers in Pasig and Marikina that often overflow. Abracosa calls the capital “a sprawling, low-lying urban floodplain.”

Meanwhile, flood-prone provinces like Pampanga, Bulacan, Pangasinan, and Tarlac have flat plains near rivers, which makes water spread more easily, said Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation (PDRF) President Butch Meily. Rain runoff from mountain ranges worsens flooding in Rizal and other provinces, Meily tells ABS-CBN.com, adding that climate change is also creating stronger storms. The Philippines is also located within the Pacific typhoon belt, which means it experiences about 20 typhoons each year.

However, both experts agree that these geographic and climate factors aren’t the main problem. “Decades of poor urban planning, catastrophic waste mismanagement, and deep-seated institutional failures have transformed a natural occurrence into a recurring national disaster,” said Abracosa.

According to Meily, excessive land use, like unnecessary roads and pavements, as well as poorly-managed drainage and waste management systems, redirects water back towards cities. A lack of floodways and drainages keeps water stuck. Urbanization reduces green spaces and wetlands, which would have naturally kept floods in check.

Making matters worse is a “massive solid waste problem,” said Abracosa. The Philippines’ reliance on single-use plastics like sachets and bottles clogs drains and other water paths, which stops floods from receding.

He adds that “this is not a simple problem of outdated infrastructure; it is a fundamental design flaw where critical infrastructure was built without respecting the natural cycle.”

Finally, and most notoriously, is the slew of substandard or nonexistent flood control projects being investigated around the country. According to Abracosa, “the most profound failure in the Philippines’ flood control efforts is not a lack of technical expertise or financial resources, but a deeply embedded culture of corruption.”

Many of the proposed projects are plagued by design flaws and weak implementation. What’s worse, said Meily and Abracosa, is that the approved flood control projects would not have solved the Philippines’ flooding problem, even if they were implemented correctly.

As of this writing, Filipinos commonly think of concrete dams, walls, barriers, and ditches when talking about flood control methods. These are “traditional hard engineering solutions,” says Abracosa, and while these may make sense conceptually, they have been “rendered useless by widespread institutional corruption.”

Execution is fragmented and substandard – and oftentimes, nonexistent.

Meily echoes Abracosa’s statements, with his organization sharing similar ideas thanks to its longstanding partnership with Dutch water management firm Deltares.

PDRF, which was formed in 2009 as a post-Ondoy initiative, believes effective flood control will come from nature-based solutions. Such projects wouldn’t just redirect or catch floodwater, but reduce the occurrences of flooding altogether.

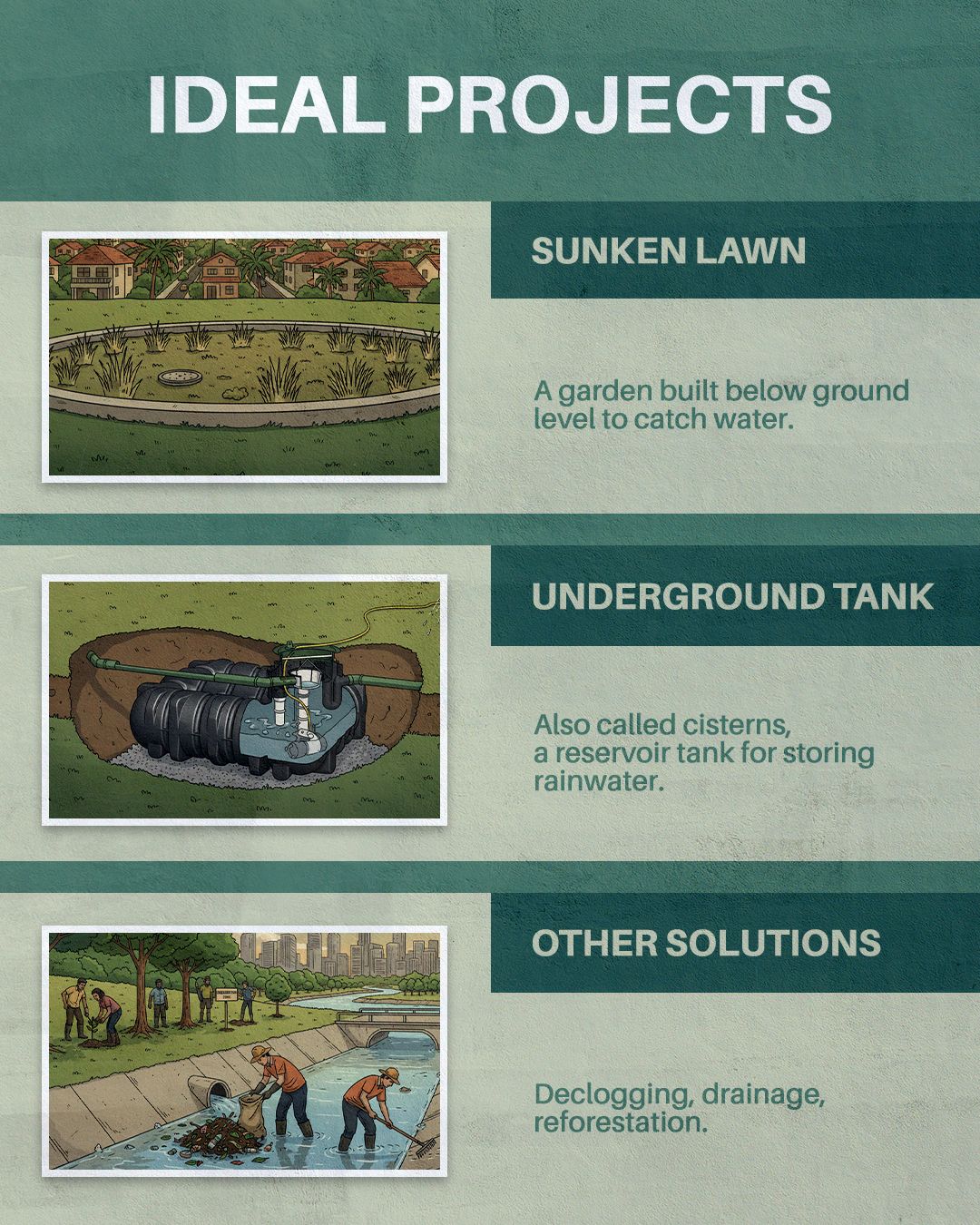

“Copenhagen has sponge parks that use green infrastructure like sunken lawns and underground tanks to manage excess water. Reforesting is important too,” Meily adds, because trees hold water and reduce the chances of a flood. Part of what makes Manila so susceptible to floods now, he said, is because so many farms have been turned into subdivisions.

While it is impossible to reverse urbanization, requiring developers to upgrade their drainage systems proves effective.

“BGC is a good example. It never floods, because back when BGC was built, then-DPWH Secretary Babes Singson constructed a five-story cistern that captures the runoff of water when it rains. LGUs can build rain catchment areas or similar cisterns to capture excess water which can also be used during the dry season,” said Meily.

When asked to name three of the most important fixes that could help Manila with its flood crises, Meily named de-clogging drainage, reforesting the Marikina Watershed, and building a spillway to move excess water from Laguna de Bay and the Marikina River to the Pacific Ocean.

Abracosa prioritized the same things: a “massive overhaul of [our] antiquated drainage system,” nature-based defenses like restoring wetlands and mangroves, and green infrastructure under the “Sponge City” model. This model focuses on accommodating and redirecting water, instead of controlling and containing it.

Projects under these initiatives would involve permeable surfaces and rainwater retention tanks, similar to the cisterns Meily discussed.

Experts believe controlling floods in the Philippines will take more than floodwalls and barriers. The country’s current approach to flood control is “so fundamentally misaligned with its geography and lifestyle that flooding would persist,” explains Abracosa.

“The solution, therefore, requires not just better maintenance, but a redesign of the urban landscape,” he concludes.

Article by Isa Martinez | ABS-CBN News